Post-Infectious IBS: Viral vs Bacterial

Introduction to Post-Infectious irritable bowel syndrome

What is PI-IBS?

Post-Infectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome (PI-IBS) is a subtype of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) that develops after an episode of infectious gastroenteritis, which may be caused by a virus or a bacterium. IBS is the most commonly diagnosed gastrointestinal disorder. Symptoms associated with IBS include abdominal pain, bloating, and altered bowel habits, such as diarrhea, constipation, or both. PI-IBS is a rather bothersome subtype of IBS in which seemingly harmless tummy troubles morph into long-lasting IBS symptoms.

To put things into perspective, studies have shown that approximately 6-17% of IBS symptoms arise after an infection. To add a little trivia, Rome III Criteria for IBS, a set of diagnostic guidelines, includes Post Infectious IBS as a recognized subtype.

Viral and bacterial culprits

Infectious enteritis, or inflammation of the intestines, can be caused by various pathogens, including viruses and bacteria. Viral infections, such as norovirus and rotavirus, are common culprits behind gastroenteritis episodes. On the bacterial side of things, some well-known offenders include Salmonella, Campylobacter, and Escherichia coli (E. coli).

The risk of developing IBS following an infection seems to vary depending on the infectious agent involved. For example, confirmed cases of bacterial infection with Salmonella or Campylobacter have a higher likelihood of leading to PI-IBS compared to viral infections. Moreover, the use of antibiotics during the initial infection may also contribute to the development of this type of IBS, as they can disrupt the delicate balance of the gut microbiome.

Common infectious agents and their molecules

Bacteria and their naughty molecules

Some common bacterial agents behind these gut-wrenching episodes include:

- Salmonella: This pesky bacterium produces a variety of virulence factors such as invasins and enterotoxins, which disrupt the intestinal lining and cause diarrhea.

- Campylobacter: This troublemaker releases a toxin called cytolethal distending toxin (CDT), which can damage the intestinal cells and lead to inflammation.

- Escherichia coli (E. coli): Not all strains of E. coli are harmful, but some like enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) produce heat-labile (LT) and heat-stable (ST) enterotoxins that can cause severe diarrhea.

- Shigella: This bacterium produces Shiga toxin, which can cause damage to the intestinal lining and lead to bloody diarrhea.

- Vibrio cholerae: The infamous cholera bacterium releases cholera toxin (CT), a potent enterotoxin that activates the production of cyclic AMP, leading to severe watery diarrhea.

Viruses and their molecular pathology

Not to be outdone by bacteria, viruses also have their fair share of microorganisms that can cause gastroenteritis. Some common viral agents include:

- Norovirus: This highly contagious virus uses a protein called VP1 to bind to host cells, causing inflammation and diarrhea.

- Rotavirus: This double-stranded RNA virus produces a nonstructural protein called NSP4, which acts as an enterotoxin and leads to diarrhea.

- Astrovirus: This single-stranded RNA virus causes gastroenteritis by producing a protein called capsid protein, which induces diarrhea by disrupting the intestinal barrier.

- Sapovirus: Similar to norovirus, sapovirus uses a protein called VPg to attach to host cells and cause gastroenteritis.

- Adenovirus: This DNA virus can cause gastroenteritis by producing a protein called fiber protein, which helps the virus enter host cells and disrupt the intestinal lining.

Microorganism | Type | Pathogenic agents |

|---|---|---|

Bacteria | Salmonella | Invasins, Enterotoxins |

Campylobacter | Cytolethal Distending Toxin (CDT) | |

E. coli | Heat-labile (LT), Heat-stable (ST) Enterotoxins | |

Shigella | Shiga Toxin | |

Vibrio cholerae | Cholera Toxin (CT) | |

Viruses | Norovirus | VP1 |

Rotavirus | NSP4 | |

Astrovirus | Capsid Protein | |

Sapovirus | VPg | |

Adenovirus | Fiber Protein |

How do viral vs bacterial infections affect the gastrointestinal system?

Different mechanisms and effects on the GI system

Pathophysiology and long-term effects of infections

Even after the resolution of the infection, the GI system can be affected by changes in the mucosal lining, inflammation, and enteroendocrine cell hyperplasia. These changes may be driven by cytokines, and the main content of the enteroendocrine cells is 5HT (serotonin), an agent that stimulates peristalsis and intestinal secretion.

The two kinds of infections also differ in their modes of transmission. Viral gastroenteritis can be contracted through the consumption of contaminated food and water or contact with contaminated materials like clothing, furniture, and utensils. Bacteria, on the other hand, can also be contracted through the fecal-oral route but may also be ingested from improperly prepared or stored food. Bacteria may produce harmful toxins that can trigger gastroenteritis, either directly or through their byproducts.

Why do different triggers require different treatments for PI-IBS?

Importance of identifying the initial infectious agent

Different treatments of PI-IBS based on the trigger

Since bacterial gastroenteritis can have a more severe impact on the gut, treatments may need to focus on restoring the physicochemical properties of the gut, such as pH, and selecting meals that do not alter motility patterns. A diet designed to support gut health and promote a balanced microbiome is essential for patients recovering from bacterial gastroenteritis. In addition to dietary interventions, behavioral and lifestyle changes may be necessary for patients who have experienced severe bacterial gastroenteritis.

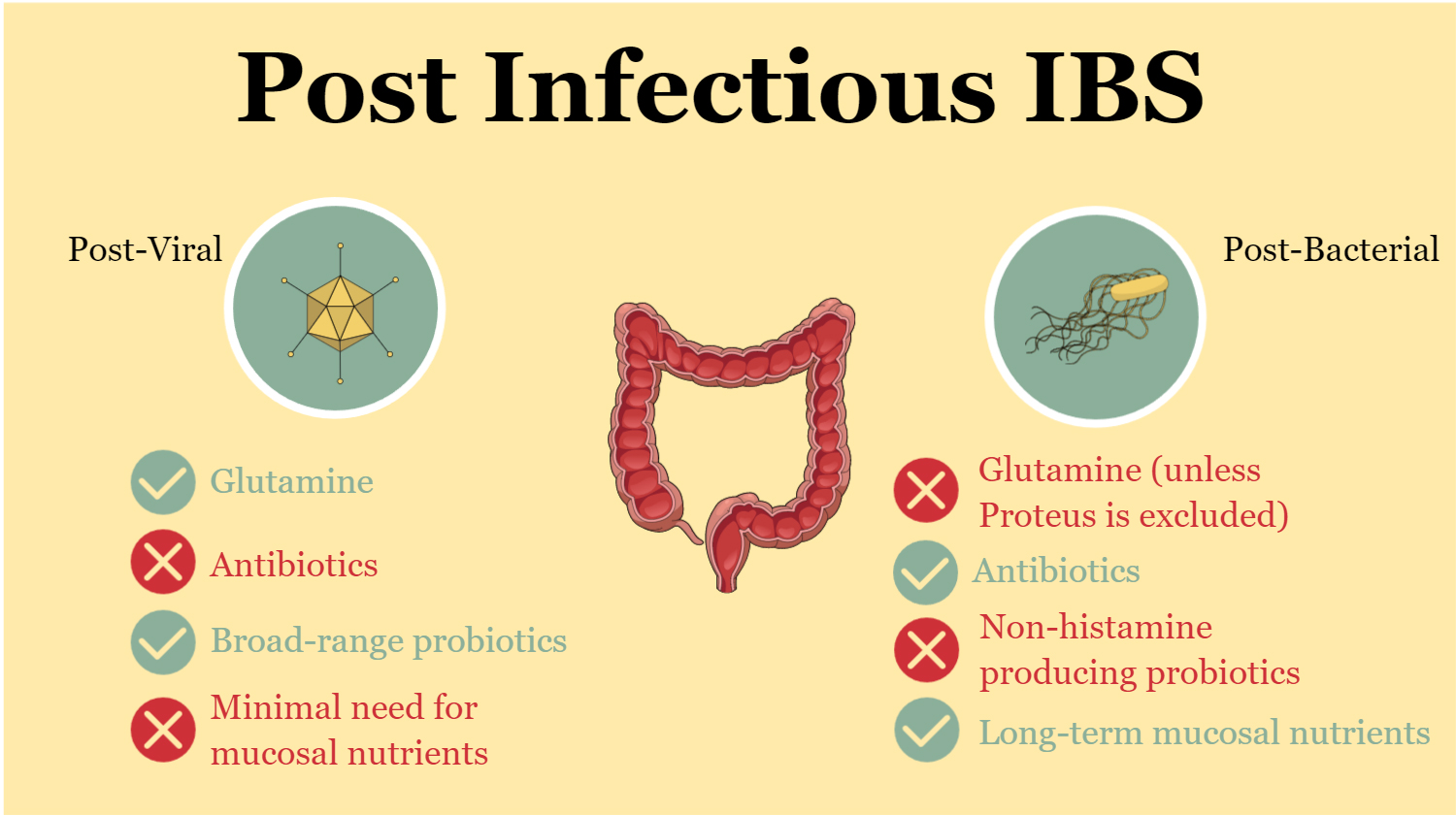

Some examples

- Glutamine: Glutamine supplementation is always beneficial for patients with post-viral IBS. On the other hand, some bacteria, such as Proteus mirabilis, utilize glutamine to survive, produce biofilms, and develop antibiotic resistance. In these cases, glutamine supplementation may not be recommended as patients may go on to develop additional symptoms.

- Antibiotics: While post-viral IBS resolves on its own, post-bacterial IBS may require antimicrobial treatments, which may cause a temporary worsening of symptoms before improvement occurs. This is due to the body’s response to the treatment.

- Different probiotics: Formulations for post-viral IBS often consist of simple combinations, such as Saccharomyces boulardii, Lactobacilli, and Bifidobacteria. In contrast, post-bacterial IBS patients may require more carefully selected probiotics due to potential mast cell activation sensitivity. Some Lactobacilli strains are histamine producers and can exacerbate symptoms in these patients.

- Need for mucosal nutrients: These nutrients, which support the health and function of the gut lining, may only be required for a few weeks in post-viral IBS cases. In contrast, patients suffering from IBS after contacting bacteria may need to maintain these nutrients for much longer periods to promote optimal gut healing and recovery.

Can COVID-19 cause PI-IBS?

Gastrointestinal involvement in COVID-19

Potential pathways for COVID-19-related PI-IBS

- Dysbiosis

- Inflammation

- Epithelial barrier dysfunction

- Increased intestinal permeability

- Visceral hypersensitivity

The Search for a Cure: Can Post-Infectious IBS Be Completely Treated?

The complex nature of PI-IBS treatment

The answer to whether post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS) can be completely treated is both yes and no, depending on various factors. As discussed, PI-IBS can result from viral or bacterial infections, and the treatment approaches for each can differ significantly. Understanding the specific mechanisms behind the development of PI-IBS and the nature of the infection is crucial for determining the most effective interventions.

Factors affecting treatment outcomes

In my experience working in gastroenterology clinics, I have observed that many parameters can eventually affect the result of any intervention for PI-IBS. The severity of the infection, the patient’s medical history, and the presence of underlying gastrointestinal or psychological conditions can all influence the success of a given treatment. Additionally, the specific strain of bacteria or virus that caused the initial infection can play a significant role in determining the appropriate course of action.

Send an email for further information or to discuss how I can help you achieve your health goals by addressing your gut health and microbiome. Book an appointment to receive personalized guidance and support, tailored to your specific needs.

FAQ

How long does post-infectious IBS last?

The duration of post-infectious IBS varies among individuals. Some people with post-infectious IBS may experience symptoms for a few weeks to months following the initial bout of infection, while others may have symptoms that persist for years. Although symptoms usually improve over time, they can fluctuate in intensity and frequency. This is why the accurate identification of the triggering microorganism and the categorization of the kind of IBS, along with proper dietary and lifestyle interventions are critical for PI-IBS treatment.

Is post-infectious IBS permanent?

Post-infectious IBS is not permanent, but its duration varies from person to person. Many individuals see an improvement in their IBS-like symptoms over time, while others continue to experience fluctuations in their bowel function for an extended period. Appropriate treatment options and lifestyle adjustments can help manage symptoms and improve the condition in the long term.

Can antispasmodics treat IBS?

Yes, antispasmodics are often used in the treatment of IBS. They work by reducing gut muscle spasms, which can help alleviate symptoms such as abdominal pain, cramping, and irregular bowel movements. Antispasmodics are typically more effective when combined with other treatments and lifestyle modifications to manage IBS symptoms but should not be used as a monotherapy to treat post-infectious IBS.

How does food poisoning develop into IBS?

Food poisoning can lead to the development of IBS in some cases, particularly when it results in a severe or prolonged bout of infection. The infection may cause changes in the gastrointestinal system, such as alterations in gut motility, increased sensitivity, and dysregulation of the gut microbiome. These changes can result in persistent gastrointestinal symptoms even after the infection has resolved.

Can post infectious IBS be cured?

There is no definitive cure for post-infectious IBS, but many people experience significant improvement in their symptoms over time. Treatment options, such as antispasmodics, dietary modifications, and stress management, can help manage and alleviate symptoms. While some individuals may continue to experience IBS symptoms long-term, others may find their symptoms diminish or resolve completely with appropriate treatment and lifestyle adjustments.

With a background in Chemistry and Biochemistry from the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Theodoros brings a wealth of knowledge in functional medicine and advanced treatments to his role. He possesses exceptional skills in analysis, pattern recognition, diagnostic translation, and storytelling. He is also FMU certified in Functional Medicine and has received training in advanced treatments from the Saisei Mirai Clinic in Japan.