LEARN EXACTLY WHY you run to the restroom after taking that antibiotic a few months ago and treat it once and for all

Antibiotics are the second-most common spark for IBS flares after a stomach bug

Large studies show that people who’ve taken several courses have roughly double the odds of being diagnosed with IBS later on, and as noted in IBSyncrasy, each drug leaves its own “microbial fingerprint,” so the fallout isn’t the same for everyone

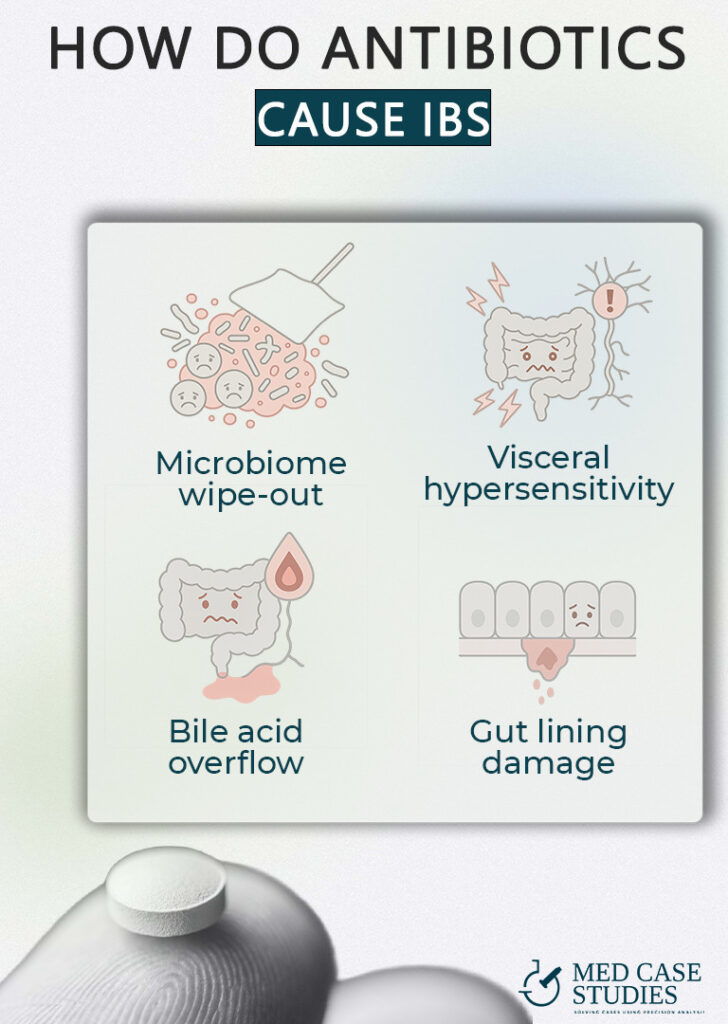

Broad-spectrum antibiotics don’t just target the bug that made you sick; they also affect commensal microbial populations that keep gas-producers and toxin-makers in check. When the good strains thin out, fast-growing species move in and change the way food ferments, setting the stage for bloating and irregular stool. A Swedish registry study found that even one or two courses raised IBS risk, and three or more pushed it even higher.

Gut nerves rely on short-chain fatty acids from beneficial microbes to stay calm. When those microbes disappear, the nerves fire at weaker stimuli, so normal digestion can feel painful. Mouse work showed that an antibiotic cocktail alone lowered the pain threshold, while adding a single Lactobacillus strain settled things back down

Some drugs wipe out the bacteria that convert primary bile acids into gentler forms. Extra primary bile reaches the colon, draws in water, and speeds transit leading to classic loose stools seen in IBS-D. A 2024 review of the gut-microbiota–bile-acid axis highlights this mechanism as a key link between antibiotics and post-treatment diarrhea. The mechanism is similar to the one linked to IBS after gallbladder removal.

Certain cephalosporins, such as ceftriaxone, thin the mucus layer and loosen the tight junctions between cells. In rat studies, just a week of ceftriaxone led to a leaky barrier and low-grade inflammation, conditions that can keep bowels swinging between sluggish and urgent.

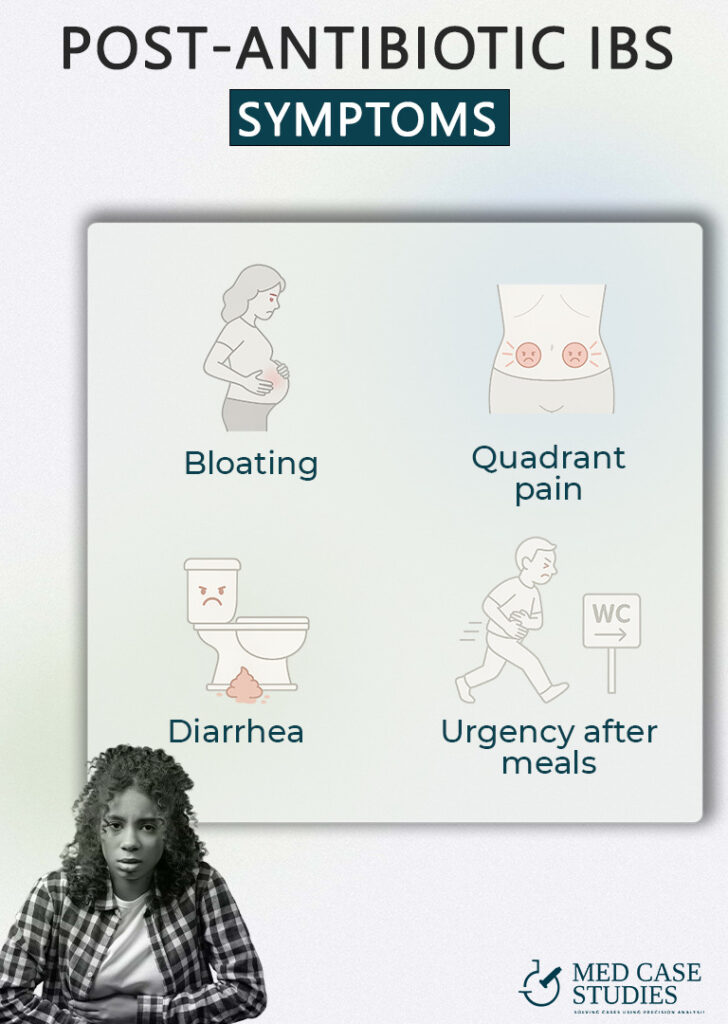

When broad-spectrum drugs empty out your “old-growth” microbes, fast-growing fermenters grab the leftover food. They pump out excess hydrogen and methane, leaving the abdomen tight by late afternoon. A 2024 review links shifts in gas-producing species directly to post-antibiotic bloating and distension

Gas rises and stalls at the colon’s two bends—the splenic flexure (left) and hepatic flexure (right). Pressure at these “bottlenecks” can cause sharp, localized aches that often ease after a big belch or bowel movement. Splenic-flexure syndrome, long considered a cousin of IBS, is the textbook example.

Certain antibiotics knock out the bacteria that convert harsh primary bile acids into milder forms. Extra bile floods the colon, drawing in water and speeding transit. The result is urgent, watery stools that can mimic a stomach bug. A 2021 review of bile-acid diarrhea lists antibiotic use as a leading trigger and explains the sodium-water pull that drives loose output

Many patients describe a “must-go-now” feeling within minutes of eating. That surge is the gastrocolic reflex doing its job. But when bile acids are high and the colon is inflamed, the reflex fires harder than usual. StatPearls notes that people with IBS show an exaggerated gastrocolic response, translating normal peristaltic waves into mad dashes for the restroom.

The timeline is all over the map. In population data, people who took three or more antibiotic courses had nearly double the odds of developing irritable bowel syndrome compared with those who never filled a prescription, and their symptoms tended to hang around longer. For some, the gut settles within a week; for others, the fallout stretches for months or even a year. A 2025 review on antibiotic-induced dysbiosis notes that shifts in the gut microbiome can linger “for weeks or even months” after the last pill, especially when diversity was hit hard at the start.

So while no clock fits everyone, the bigger the microbial shake-up, the longer it takes for digestive health to feel normal again and the more carefully we have to watch which gut bacteria gain the upper hand.

The effect of antibiotics on the gut microbiota is one big reason people sometimes develop IBS, including the stubborn post-infectious IBS that shows up weeks after the original bug is gone. Here’s how four drug families set the stage for ongoing digestive trouble and classic IBS symptoms.

Over the past decade I’ve tracked more than 1,400 ibs patients who came to clinic convinced their “quick” antibiotic treatment had left them worse off than the original infection. When they stick to the full plan (diet, targeted probiotics, and a short course of non-absorbed antiboitic where appropriate) most notice the first baby-step improvements by week two and reach solid, day-to-day comfort somewhere around the 40-day mark. That slow climb is real: symptom-score charts from rifaximin trials show the average responder curve rising almost invisibly for the first 15 days before breaking clear of placebo at week four. Missing doses, on the other hand, is the fastest way to stall progress. A 2021 real-world study found price, mild bloating, and plain old forgetfulness were the top adherence killers in IBS care.

Still, even perfect adherence isn’t a magic shield. My clinic’s relapse log spikes every winter, right in step with norovirus season. One Norwegian cohort showed that 13 % of people who caught norovirus went on to meet criteria for post-infectious IBS three months later. Antibiotics may weaken the gut wall’s viral defenses by thinning out Bacteroides, leaving a viral bug free to tip an already jumpy bowel back into full flare. Spring isn’t always safer. Emerging data link adenovirus gastroenteritis to PI-IBS as well, probably through the same inflammatory cascade that rattles sensory nerves and tight junctions.

The other repeating pattern is diet. Many newcomers report that a strict low-FODMAP plan takes the edge off gas in days, so they keep it going for months. But breath-test work and sequencing studies confirm that long-term restriction drains bacteria in the gut, especially the carbohydrate-loving Bifidobacterium group. Less short-chain-fatty-acid fuel means nerves stay excitable and the colon stays irritable, which is why my follow-up scripts always include a timeline for gently expanding foods once symptoms settle.

When recovery drags past the two-month line, stool tests usually show one of two hallmarks: (1) runaway Enterobacteriaceae seeded by earlier broad-spectrum courses, or (2) a microbiome still wiped of keystone species. A 2025 review of the effect of antibiotics on transplant patients’ microbiota underscored how wide these wipe-outs can be, with some taxa still missing six months later. In the longest cases we add another non-systemic antibiotic plus a multi-strain probiotic to restore gut health; an updated NEJM analysis of rifaximin retreatment documented meaningful gains even in third-round users.

Zooming out, every chart I keep reminds me that improvement is gradual and sometimes quiet enough that patients need weekly graphs to believe it’s happening at all. Yet with consistent support most cross a tipping point around day 40 where the good days finally outnumber the bad and that’s usually when the gut microbiota starts to look recognisable again. In the few who don’t, digging for latent infections or re-examining earlier antibiotic treatment choices is the next logical step, because lingering drug residues and the gaps they leave behind are often the last roadblock in getting ibs under lasting control.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |