Post-Infectious IBS diet – Low FODMAP Is NOT a long-term solution

Post-Infectious IBS Case Study

Each subtype of IBS, including post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS), has unique microbiome signatures and structural and biochemical alterations, which can influence symptoms and treatment options. That’s why generic diet plans do not cover the specific needs of each patient and most of the time lead to symptom-rebound upon reintroduction of eliminated foods. Besides, the majority of the patients that come to my office have already tried 2-3 general diets that have read online or were suggested to them by a dietitian. Most of the time it didn’t work. Developing a personalized dietary plan is crucial for effectively managing IBS symptoms and addressing the unique characteristics of each subtype.

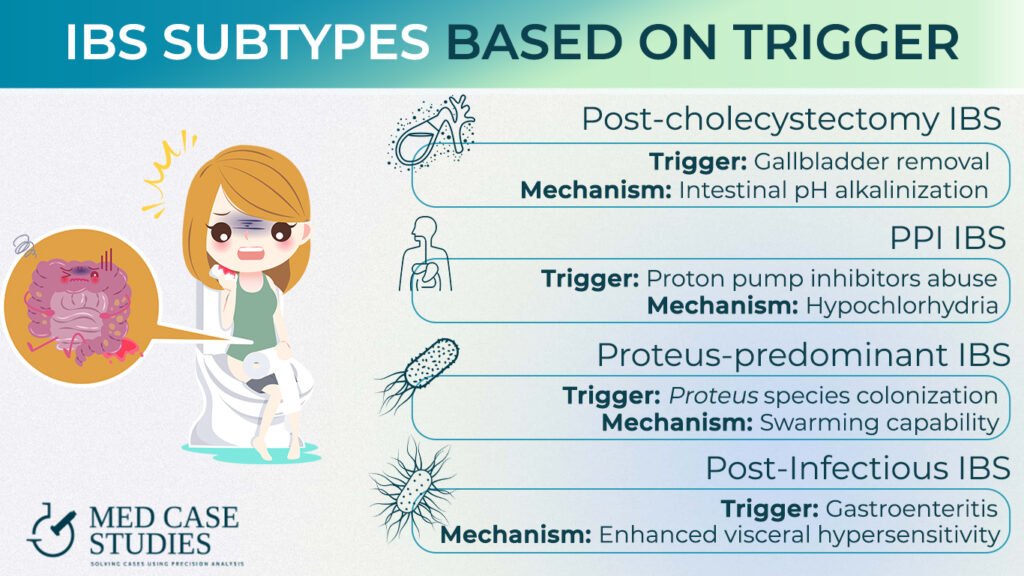

Irritable bowel syndrome subtypes based on the initial trigger

IBSyncrasy

Every IBS is unique

Characteristics of some IBS subtypes

Post-cholecystectomy IBS

Unique trait: Intestinal pH alkalinization

Post-cholecystectomy IBS occurs after the removal of the gallbladder, which can lead to altered bile acid metabolism and intestinal pH alkalinization. This change in pH has a huge impact on the gut microbial ecology and contributes to the development of IBS symptoms.

PPI-IBS

Unique trait: Transient hypochlorhydria

PPI-IBS is triggered by the overuse of Proton Pump Inhibitors, which can cause hypochlorrhydria or reduced stomach acid production. Hypochlorrhydria impairs digestion and absorption of nutrients, altering the microbial balance

Proteus IBS

Unique trait: Swarming ability

Proteus-predominant IBS is triggered by the colonization of Proteus bacteria in the gut, which have a unique swarming ability in the presence of excess glutamine. This disruption leads to several biochemical alterations in susceptible patients that will eventually develop PI-IBS

Post-Infectious IBS

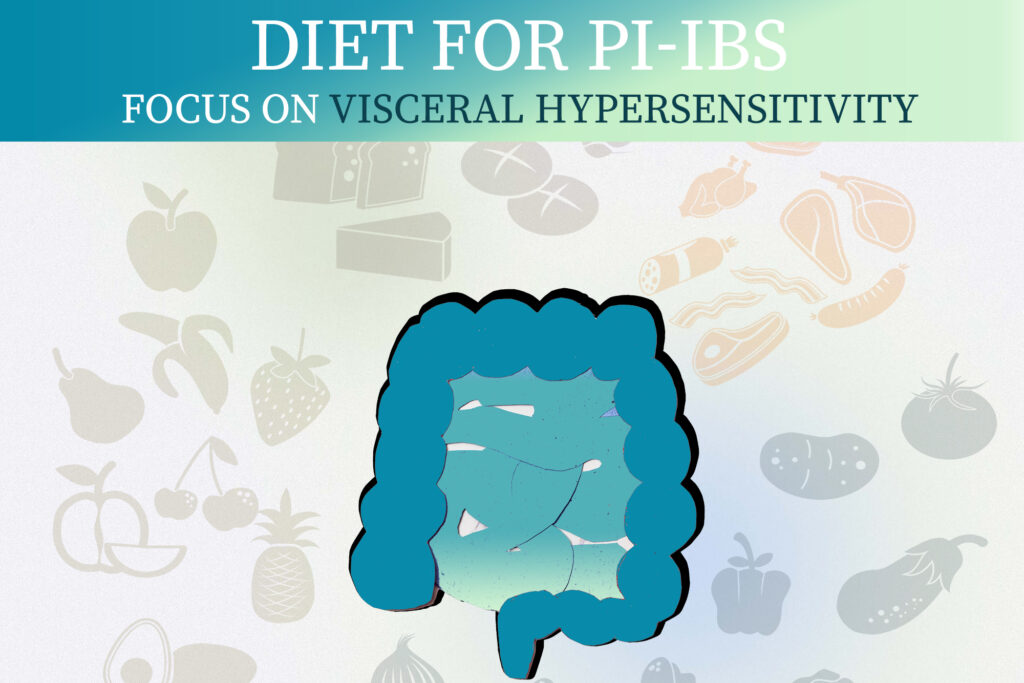

Unique trait: Enhanced visceral hypersensitivity

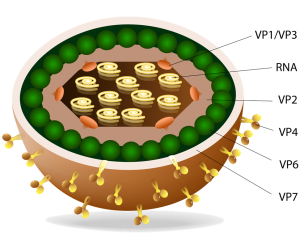

PI-IBS, caused by bacteria like Salmonella or Campylobacter, or viruses like Norovirus is characterized by increased sensitivity of the gastrointestinal tract to various stimuli, leading to abdominal pain and discomfort. This hypersensitivity may result from altered gut motility and sensation, as well as imbalances in the gut microbiome.

Diet interventions tailored to post infectious IBS

Post-Infectious IBS Recovery Time: 7 Tips for Faster Healing

Post-Infectious IBS Recovery Time: 7 Tips for Faster HealingDesensitization through dietary choices

The heightened pain sensitivity in PI-IBS is linked to an overactive enteric nervous system and increased responsiveness of pain receptors in the gut. Foods that stimulate pain receptors or promote gas production can exacerbate this sensitivity. Therefore, dietary choices should focus on minimizing these triggers. For example, avoiding gas-producing foods such as beans, cabbage, and carbonated beverages can help alleviate discomfort. This is not a healing process, but symptomatic relief until the treatment gives results.

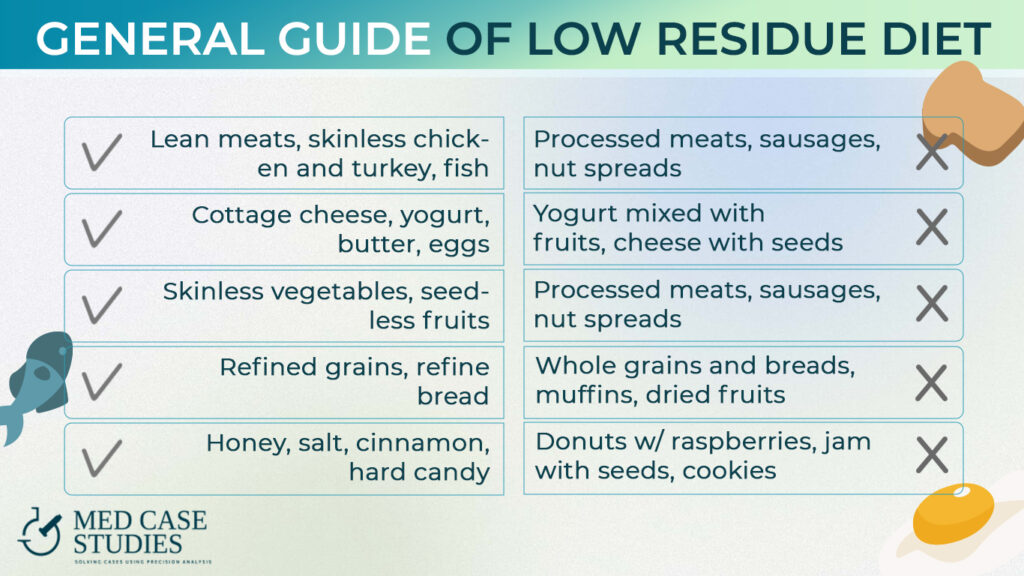

Low-residue diet for PI-IBS

A low-residue diet (LRD) can be particularly useful for PI-IBS patients. This diet limits the intake of fibrous and indigestible food components, reducing the amount of undigested material that reaches the colon. By decreasing the volume of digestive residues, the LRD reduces the pressure and distension within the large intestine, which in turn can alleviate the visceral hypersensitivity experienced by PI-IBS patients.

Foods recommended in an LRD include refined grains, lean meats, and well-cooked vegetables without skin or seeds. On the other hand, high-fiber foods, raw vegetables, and fruits with skin should be avoided, as they can contribute to increased residue in the colon.

Low-FODMAP diet: A common but temporary solution

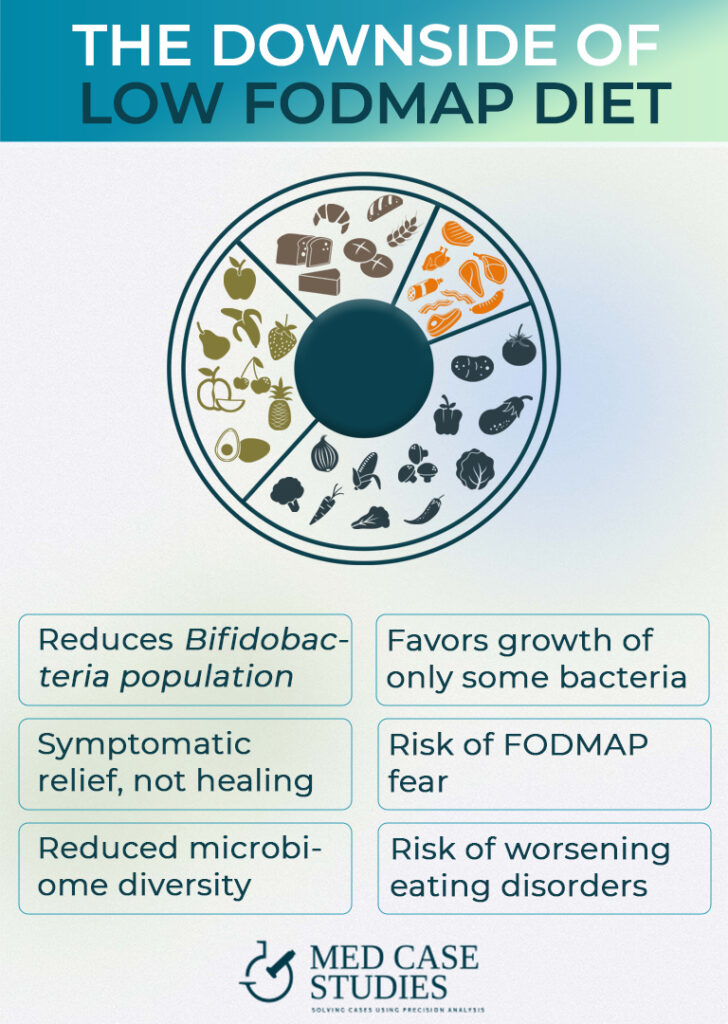

The Low-FODMAP diet is often regarded as the holy grail for IBS and, according to some practitioners, for several inflammatory bowel diseases. Despite its popularity, the low-FODMAP diet is not a long-term solution. This is due various reasons, including its impact on the gut microbiome and potential risks for individuals with eating disorders.

Limitations and risks of low-FODMAP diet

Reduction of bifidobacteria: Low-FODMAP diets (LFD) limit the intake of fermentable carbohydrates, which leads to a reduction in bifidobacteria, essential for maintaining a healthy GI tract.

Symptomatic reduction due to histamine reduction: While the diet may alleviate symptoms through the reduction of histamine levels, it does not address the root cause of the symptoms.

Inhibition of probiotic strains: Some beneficial bacterial strains may not thrive in an LFD environment, potentially compromising gut health.

Fear of FODMAPs: Individuals may become apprehensive about reintroducing important FODMAP-containing foods, which can lead to nutrient deficiencies.

Reduced microbiome diversity: Prolonged adherence to LFD may reduce gut microbiota diversity, increasing the risk of developing other health issues.

Worsening eating disorders: A highly restrictive diet like the LFD may exacerbate existing eating disorders.

FAQ

Are there different types of IBS?

Yes, there are different types of IBS. They can be categorized based on bowel movement patterns, such as constipation (IBS-C), diarrhea (IBS-D), and mixed (IBS-M). Additionally, IBS subtypes can be identified based on the initial trigger, such as post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS), PPI-IBS, Proteus-predominant IBS, and post-cholecystectomy IBS (following gallbladder removal).

Is there a specific diet for IBS?

There is no one-size-fits-all diet for post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS) as each subtype presents unique biochemical, microbiological, and structural signatures that require personalized approaches. To effectively manage symptoms, individuals with IBS should work with a healthcare professional to develop a tailored dietary plan that addresses their specific needs and considers the unique characteristics of their IBS subtype. This ensures optimal symptom relief and long-term management of the condition.

With a background in Chemistry and Biochemistry from the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Theodoros brings a wealth of knowledge in functional medicine and advanced treatments to his role. He possesses exceptional skills in analysis, pattern recognition, diagnostic translation, and storytelling. He is also FMU certified in Functional Medicine and has received training in advanced treatments from the Saisei Mirai Clinic in Japan.