Proteus mirabilis is all about gas, flatulence and histamine-related symptoms.

find the solution in IBSYNCRASY

-

DIAGNOSIS

TREATMENT

-

FOLLOW UP

Finding Proteus mirabilis in your stool means this bacteria has moved beyond its usual link with urinary infections and is colonizing your gut. It drives IBS flares with gas, bloating, urgency, and pain. If your symptoms spiked after antibiotics or a stomach bug, this bacteria may have taken the open seat.

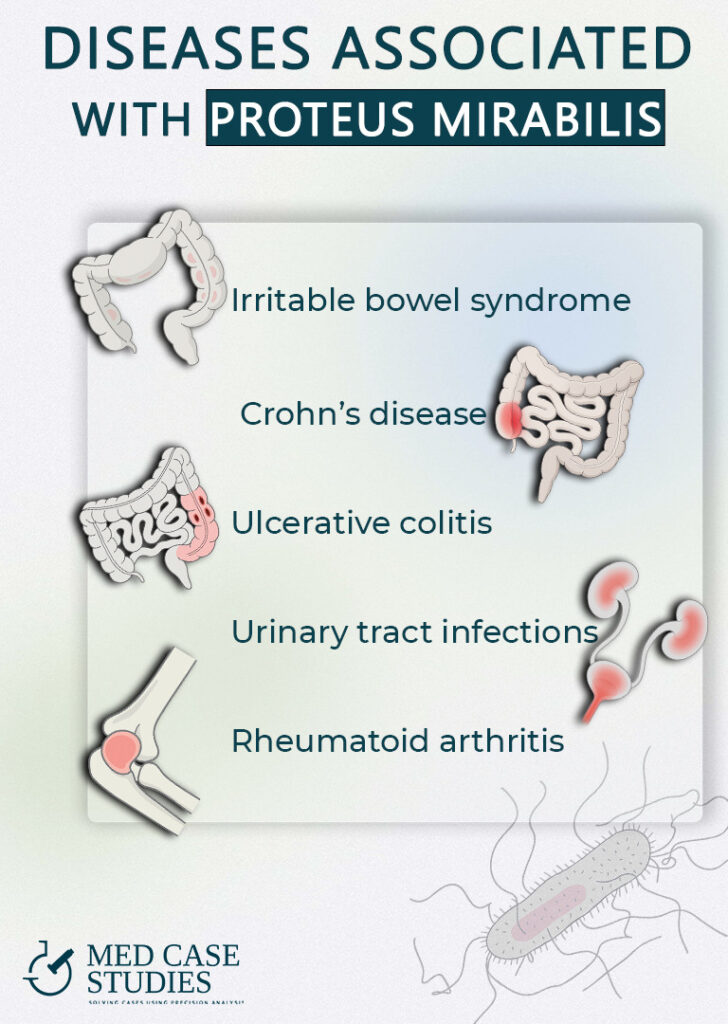

Proteus mirabilis is a gram-negative bacterium best known for urinary tract infection. Finding mirabilis in stool means this pathogen is present in your gut and almost certainly adds to symptoms. Proteus mirabilis carries notable virulence factors such as urease, adhesins, toxins, biofilm formation, and swarming motility. And these are the exact mechanisms it uses to produce bloating, quadrant-pain, diarrhea and sometimes urgent defecation.

I have been detecting Proteus spp live at low levels in the human gastrointestinal tract for over 2 decades and although it has been linked mostly to inflammatory reactions, it can also be the cause of insisting IBS symptoms. Check out the specific Proteus-IBS case studies to see how common it is.

In clinics working with IBS and IBD, this organism turns up in a subset of stool tests. In day to day practice like mine in gastro clinics, you might see it in roughly 15% of IBS stool specimens, and far more often in ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s. That pattern fits the literature showing enrichment during gut inflammation. Think of it as an opportunist that takes the open seat when other gut bacteria are disrupted.

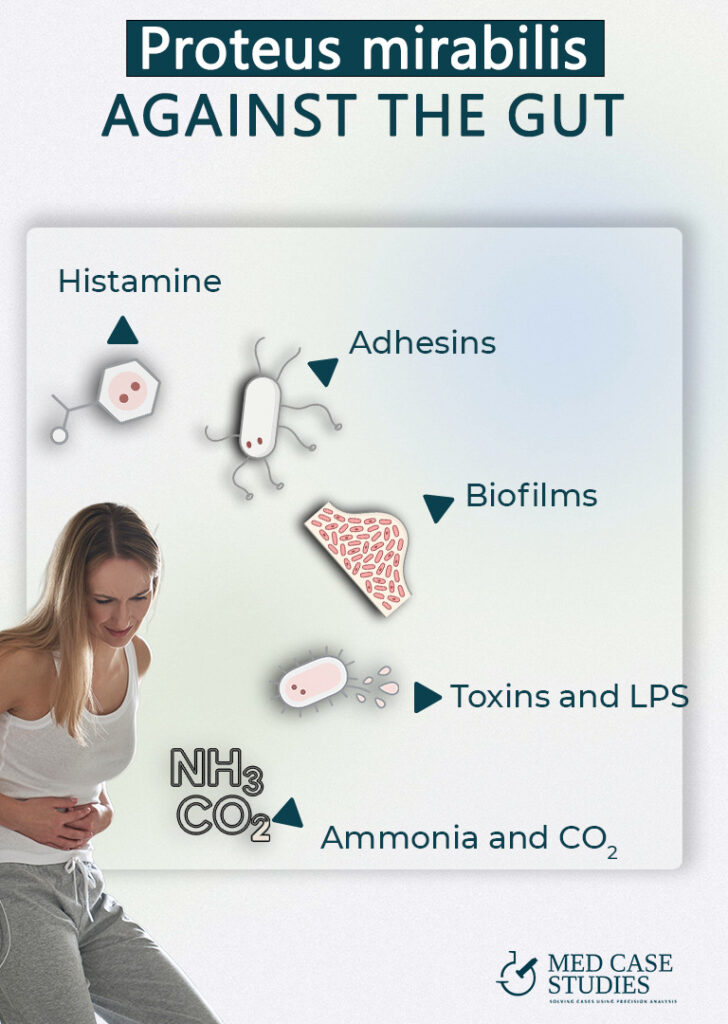

Why symptoms flare: urease from P. mirabilis splits urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide. Ammonia raises pH and irritates mucosa, while gas adds to bloating and pressure. Swarming and biofilms help the organism spread across surfaces and resist clearance. LPS and other factors can nudge immune pathways and sensitise nerves, which feeds pain and stool changes in IBS. These mechanisms are well described in UTIs and apply to the gut, as well.

DIAGNOSIS

TREATMENT

FOLLOW UP

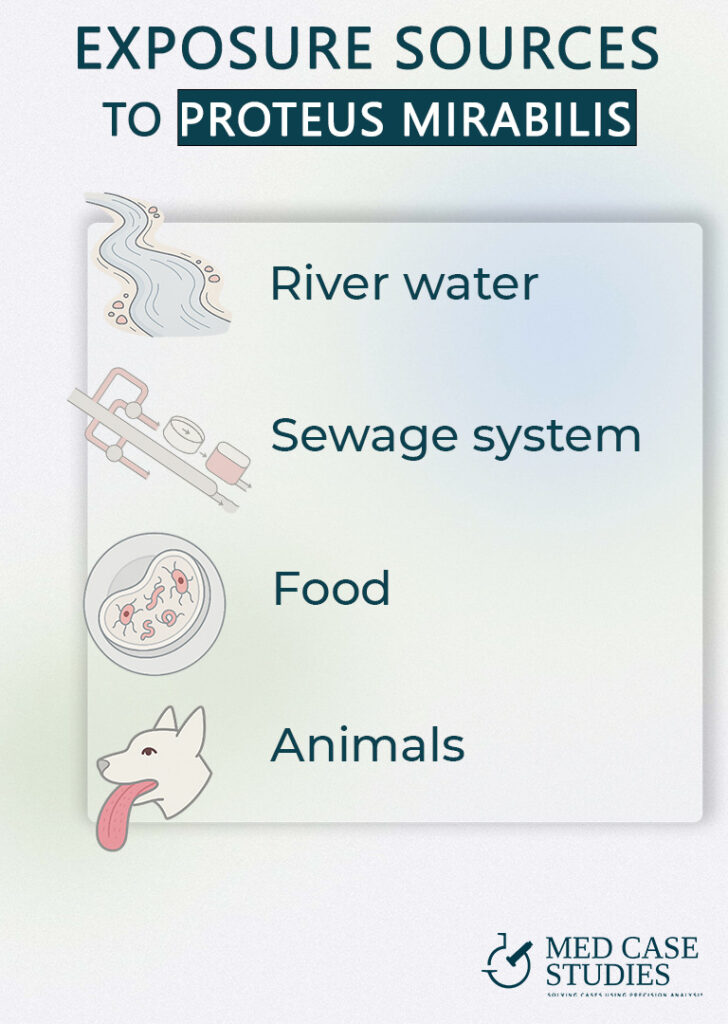

When broad-spectrum drugs empty out your “old-growth” microbes, fast-growing fermenters grab the leftover fooa It survives in soil, sewage, rivers, and seawater. Recreational water can expose you if you swallow lake or river waterd.

It has been isolated from retail meat and aquatic products, especially poultry, and has been linked to sporadic foodborne illness. Cross contamination in kitchens adds risk.

Fecal to hand to mouth spread happens with poor hygiene. Animal feces can be a reservoir.

Proteus mirabilis can sit in the gastrointestinal tract as a quiet reservoir. It builds biofilms and clings to tissue, which makes clearance harder. In IBD models it expands when the mucus layer is thin and inflamed, and that same ecology can exist in IBS after infections or antibiotics. This is why symptoms often swing back after short courses.

Repeated stool PCR may show ups and downs. You might get a negative result, then counts return as the mucosa remains vulnerable. My experience matches this pattern. You improve when you lower the load and repair the lining at the same time. Proteus mirabilis also shows rising antibiotic resistance, and biofilms blunt drug effect, so full eradication is uncommon. This is why reduction and control is much better in the long run compared to one shot cure.

A practical plan often mixes broad spectrum antibiotic coverage guided by culture or PCR trends, plus targeted probiotics and a careful diet. Most cases need a three month window to calm inflammation and restore flora.

In-vitro work shows activity against Gram-negative bacteria, including P. mirabilis. In one isolate set, oregano oil, carvacrol, and thymol achieved low MICs against P. mirabilis alongside other pathogens. The main actives, carvacrol and thymol,disrupt bacterial membranes and quorum-sensing, and related work in Proteus spp. also points to effects on motility/swarming, a key virulence trait.

Allicin inhibits P. mirabilis growth, urease activity (which drives alkaline urine/stone risk), and biofilm formation in vitro, aligning with symptom clusters where gas and high urinary pH are prominent. Because allicin is chemically unstable, standardized preparations matter

Evidence spans broad antibacterial and anti-adhesive effects (e.g., reduced uropathogen adhesion/invasion), with signals against Proteus species in secondary sources; it also modulates gut microbiota in ways that may indirectly lower Enterobacterales burden. Mind drug interactions: berberine can inhibit CYP3A4/P-gp and has clinically raised cyclosporine levels

Medical-grade Manuka honey reduces P. mirabilis biofilm viability across a range of concentrations and has shown prevention of early biofilm attachment relevant to catheter-associated settings. Consider only sterilized, clinical products (not kitchen honey)

Cinnamaldehyde demonstrates antipathogenic activity against P. mirabilis, inhibiting swarming motility and urease (two core virulence factors) and showing antibiofilm effects in vitro. Because essential oils and isolates can be caustic, internal use should be clinician-directed

Urease. P. mirabilis makes a potent urease that splits urea into ammonia and CO₂. That ammonia bumps urine pH upward, which can sting, mess with the mucus layer, and set the stage for mineral crystals (think struvite) and stone formation. The gas and crystals can irritate tissue and even encrust catheters, so symptoms like pressure, bloating, urgency, and pain often flare when urease is cranking.

Swarming and biofilm. This bug “swims as a team”: swarming cells elongate, get extra flagella, and spread fast over surfaces like the gut mucosa. Once there, they build biofilms, sticky, protective communities that block antibiotics and immune cells from getting in.

Adhesins. MR/P fimbriae act like tiny grappling hooks so P. mirabilis can latch onto the gut. Strong adhesion helps the bacteria colonize and resist being washed out. It also keeps local inflammation simmering, which is why urgency and discomfort can feel out of proportion to what labs sometimes show.

Toxins. Hemolysin punches holes in host cell membranes, and LPS (endotoxin) dials up the body’s alarm system giving rise to cytokines, swelling, and pain. Together, they amplify irritation, make nerves more sensitive, and can turn a mild bloating into a “why does this hurt so much?” situation.

Histamine (host response amplifier). Histamine release can shoot up when LPS and tissue damage poke mast cells and other immune cells. More histamine = more itch, burning, urgency, and pain sensitivity, especially in patients who are already histamine-reactive.

Start with barrier support that does not include glutamine. Proteus mirabilis can trigger swarming in response to excess L-glutamine, so you skip L-glutamine during treatment. Use food first and lining-friendly options instead. Think soluble fiber, omega-3s, polyphenol-rich foods, and sleep.

Layer antimicrobials rather than a single agent. Combine options that hit biofilms and metabolic paths in mirabilis strains. Expect variability across strains of Proteus mirabilis and even between proteus vulgaris and P. mirabilis. Biofilms and antibiotic resistance mean you aim for reduction and control, not instant eradication.

Choose probiotics with a low histamine profile. Some lactobacilli can produce histamine. Favor bifidobacteria or specific lactobacillus strains with supportive data and monitor your response. If histamine symptoms flare, pause and switch.

Hold alcohol while you treat. Alcohol can loosen tight junctions and raise intestinal permeability, which works against healing.

Eat to starve the bug and calm IBS. Limit simple sugars because P. mirabilis ferments glucose with gas in the gastrointestinal tract. Re-challenge foods later with a plan.

You likely picked up Proteus mirabilis from the environment. Proteus species live in soil, water, sewage, animals, and the human gut. Exposure happens when you swallow lake or spring water, eat contaminated meat or fish, or via hand to mouth transfer of pathogenic bacteria

Yes. Mirabilis is a gram-negative bacterium that can inflame the human gastrointestinal tract. In vitro and in vivo studies link P. mirabilis to intestinal inflammation, and diarrheagenic mirabilis bacteria have been reported. In my practice, its presence in stool often tracks with IBS flares and loose stools

In stool it is annoying and slow to clear, but if you are not immunocompromised it is usually not dangerous. The bigger risks are urinary tract infection, stones, or invasive disease, which need medical care. Outpatient management is typical for gut colonization

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |